Graffiti vs Street Art Identifier

What is this tool?

Use this interactive to determine if an artwork is more likely graffiti or street art based on key characteristics. Answer the questions below to see which category it fits best.

Artwork Analysis

Answer the questions above to see analysis results.

Ever walked past a colorful wall and wondered whether you were looking at graffiti or street art? It’s a question that pops up more often than you think, especially as cities embrace murals and artists claim public space. While the terms are sometimes tossed around interchangeably, they actually describe two distinct practices with different histories, goals, and techniques.

What Exactly Is Graffiti?

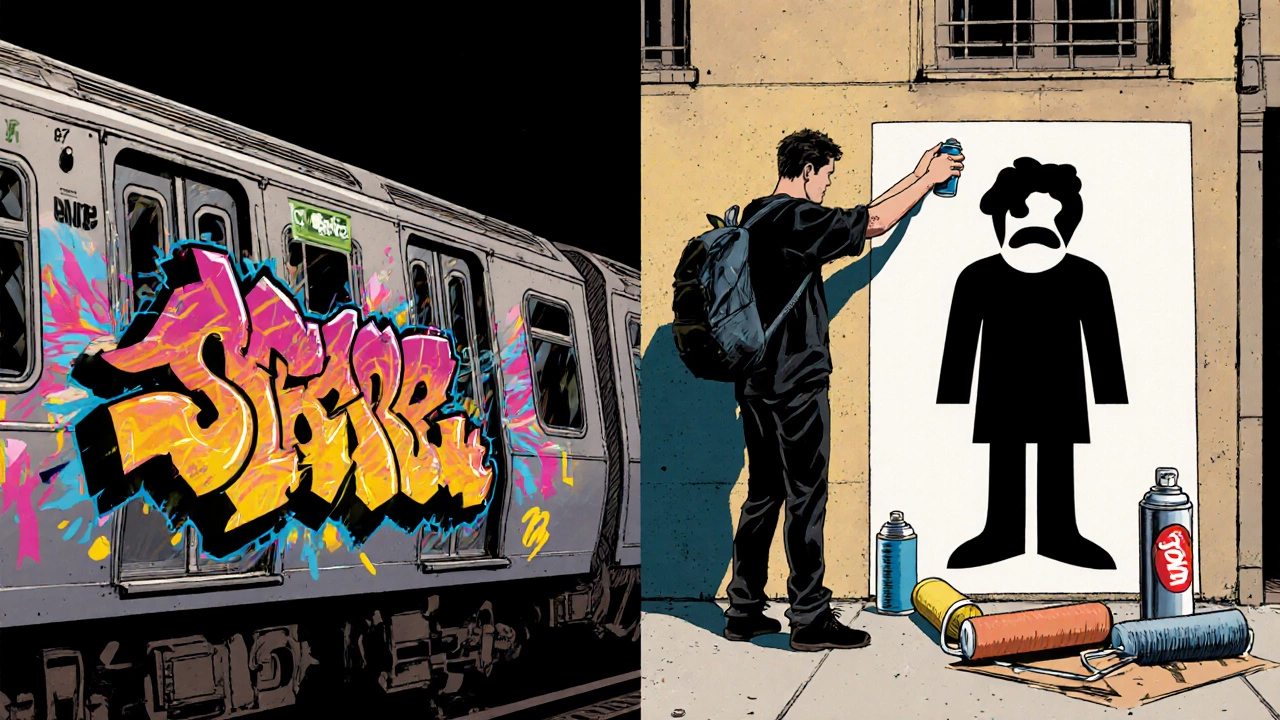

Graffiti is a form of visual expression that originated in the underground culture of the 1970s, characterized by stylized lettering, spray paint, and an emphasis on speed and spontaneity. Early pioneers tagged subway cars in New York, leaving signatures-known as tags-to announce their presence. The core idea was anonymity combined with a rapid execution: a quick splash of color that could be done in seconds before a train or a security guard turned the corner.

Graffiti is deeply rooted in hip‑hop culture, sharing its origins with break‑dancing, DJing, and MCing. It grew out of a desire to claim visibility in a world that often ignored marginalized youth. The language of graffiti is its own alphabet, with letters stretched, interlocked, and filled with vibrant gradients. Classic styles include “wildstyle” (complex, overlapping letters), “bubble letters,” and “throw‑ups” (simple, quickly executed outlines).

Defining Street Art

Street art is a broader umbrella term for any artistic activity produced in public spaces that aims to engage the broader community, often with a clear visual narrative or social message. Unlike graffiti, street art doesn’t rely on stylized lettering. Artists use stencils, wheat‑pasting, mosaics, sculptures, and large‑scale murals. The emphasis is on the image rather than the signature, and pieces are usually more elaborate, taking hours or days to complete.

Street art often seeks dialogue with passersby, commenting on politics, consumerism, or local history. Famous practitioners like Banksy use satire to provoke thought, while others simply beautify neglected alleys. The intent can range from pure aesthetic improvement to overt activism.

Historical Roots and Cultural Context

- Graffiti emerged from inner‑city youth movements, especially in New York and Philadelphia during the 1970s. It was a rebellion against social invisibility and a way to mark territory.

- Street art gained mainstream traction in the 1990s and 2000s as galleries began to showcase muralists and as cities launched public art programs.

- Both forms intersect with hip‑hop culture, but graffiti’s DNA is more about personal tags, while street art leans toward collective narratives.

Legal Landscape: Walls, Permissions, and Consequences

One of the biggest practical differences lies in legality. Graffiti is often illegal when done on private or municipal property without permission. Artists risk fines, community service, or even arrests. Many cities have designated “legal walls” where writers can spray paint without repercussions, turning a potential crime scene into a community canvas.

Street art, especially large murals, is frequently commissioned. Municipalities, corporations, and NGOs fund projects to revitalize blighted neighborhoods. This official backing means street artists can work openly, sometimes under contracts that stipulate length, theme, and maintenance.

Technique Toolbox: From Spray Cans to Stencils

| Aspect | Graffiti | Street Art |

|---|---|---|

| Main Medium | Spray paint, markers | Spray, stencil, wheat‑paste, mosaic, paint rollers |

| Typical Duration | Seconds‑to‑minutes | Hours‑to‑weeks |

| Primary Focus | Lettering, signature | Image, narrative, social message |

| Legal Status | Often illegal, unless on legal wall | Often commissioned or permitted |

Economic Impact and Market Value

Graffiti has historically been treated as vandalism, but over the past two decades it’s entered the art market. Pieces that started as illegal tags have fetched six‑figure sums at auction when they’re documented on canvas or preserved as murals. Artists such as Keith Haring transitioned from subway tags to celebrated gallery works.

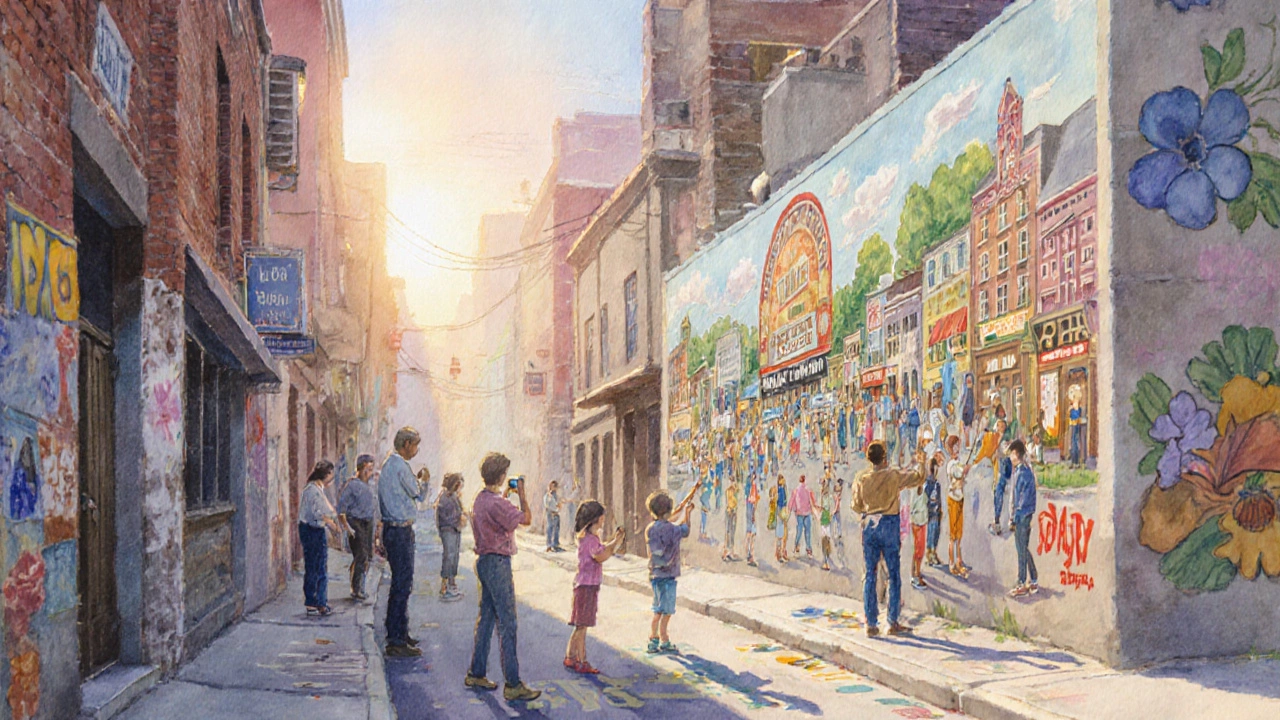

Street art enjoys a more straightforward commercial path. Cities allocate budgets-sometimes millions of dollars-for large murals that boost tourism and local pride. Companies commission street‑style graphics for advertising, blending brand storytelling with an authentic urban feel.

Community Perception: From Nuisance to Cultural Asset

Public opinion varies widely. Long‑time residents might view a spray‑painted tag as a nuisance, while younger audiences see it as a vibrant expression of city life. When a wall transforms from a blank concrete slab into a colorful tableau, the same space can shift from eyesore to Instagram hotspot.

Community‑led projects often bridge the gap. Programs that invite local youths to create legal street art reduce illegal graffiti while fostering pride. Such initiatives demonstrate that the line between the two forms isn’t just legal-it’s also social.

Key Takeaways

- Graffiti centers on stylized lettering, speed, and often operates outside the law.

- Street art focuses on imagery, narrative, and is frequently commissioned or permitted.

- Both share urban roots, but they diverge in technique, intent, and legal context.

- Legal walls and public art programs blur the boundaries, turning illegal tags into celebrated murals.

- Understanding the difference helps viewers appreciate the cultural, economic, and social layers behind every splash of color.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is graffiti always illegal?

Not always. Many cities have designated legal walls where artists can spray paint without fines. Outside those zones, unauthorized graffiti is typically considered vandalism.

Can street art be removed?

Yes. While many murals are protected by local ordinances, they can still be painted over or removed if the contract ends or if the property changes hands.

Do graffiti artists ever transition to street art?

Many do. Artists like Banksy started with tagging before moving into large stencil pieces and commissions. The skills overlap, and the shift often brings legal and financial benefits.

What materials are essential for street art?

Beyond spray cans, street artists use stencils (often cut from cardboard or Mylar), wheat‑paste posters, acrylic paints, rollers, and sometimes mosaics or found objects.

How does the art market value graffiti vs street art?

Street art typically commands higher prices when sold as canvases or prints because it’s often created with the artist’s permission and enjoys greater mainstream acceptance. Graffiti works that entered galleries can also fetch high prices, but they usually require a legal avenue for sale.